For Elizabeth Riley, Executive Director of the Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency (CDEMA), the Atlantic hurricane season can be an especially busy time. The agency coordinates and provides disaster response and relief and encourages risk reduction efforts. This year, in addition to providing aid during the pandemic and after storms and flooding in the region, CDEMA has helped victims of the La Soufrière volcano eruption in St Vincent and the major earthquake in Haiti. Our conversation in mid-September focused on issues affecting Caribbean coasts, from the difficulties of modelling the interactions when complex coastal processes are at work… to making weather forecasts clear to the public at risk… to the effects of climate change.

For Elizabeth Riley, Executive Director of the Caribbean Disaster Emergency Management Agency (CDEMA), the Atlantic hurricane season can be an especially busy time. The agency coordinates and provides disaster response and relief and encourages risk reduction efforts. This year, in addition to providing aid during the pandemic and after storms and flooding in the region, CDEMA has helped victims of the La Soufrière volcano eruption in St Vincent and the major earthquake in Haiti. Our conversation in mid-September focused on issues affecting Caribbean coasts, from the difficulties of modelling the interactions when complex coastal processes are at work… to making weather forecasts clear to the public at risk… to the effects of climate change.

Ms. Riley has spent two decades at CDEMA, which has 19 partner states, and has taken a leadership role in coordinating responses to every major regional disaster since 2004. She was named Executive Director in June of this year. Two of the stalwart tools Ms Riley clearly favours in her work are strong communication and collaboration. “One of the things CDEMA works on is horizontal cooperation. It’s one of our principles,” she explains.

Communication and Collaboration

While building coastal resilience is not directly included in CDEMA’s mission, saving lives and reducing losses from disasters are at the forefront. Elizabeth Riley is clear and well-versed in the possibilities and the challenges of mitigation measures. “One of my perceptions is that when you’re dealing with a coastal zone, you’re dealing with a sensitive zone. A lot of the requirements in the design of coastal mitigation measures require a lot of research and modelling so that you can get a sense as to what the impact or potential impact of the intervention will have on the coastlines or on other parts of the shoreline. The expertise to be able to understand, interpret, and make decisions based on what those models show does not reside everywhere in the Caribbean.”

While building coastal resilience is not directly included in CDEMA’s mission, saving lives and reducing losses from disasters are at the forefront. Elizabeth Riley is clear and well-versed in the possibilities and the challenges of mitigation measures. “One of my perceptions is that when you’re dealing with a coastal zone, you’re dealing with a sensitive zone. A lot of the requirements in the design of coastal mitigation measures require a lot of research and modelling so that you can get a sense as to what the impact or potential impact of the intervention will have on the coastlines or on other parts of the shoreline. The expertise to be able to understand, interpret, and make decisions based on what those models show does not reside everywhere in the Caribbean.”

To the question of whether Caribbean countries could share information and experience in the area of coastal resilience, she quickly nods toward the tool of collaboration, “It really helps if you can access technical expertise from a sister country,” That is especially true since so many, if not most, of the Small Island Developing States have limited resources and funding for resilience measures. While each shoreline is different, lessons learned on one coast about infrastructure, nature-based solutions, engineering and modelling techniques, and knowledgeable practitioners can help reduce risk for others. A forum to facilitate the dissemination of such information is a project to consider.

Compounding Challenges

Compounding Challenges

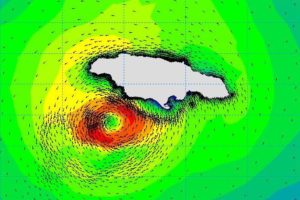

The accelerating rate of climate change and an attributable increase in the number of severe weather events is leading to challenging, and often confusing, interactions, especially on the coast. “I don’t know if it’s climate change or climate variability,” Riley says, “The complex interactions that can take place in the coastal zones, particularly when you have the combination of the surge and the inland flooding… it comes at you from all sides. When you’re having a surge with a tropical storm, and you’re having significant rainfall over land which is not permitted to flood out to the sea, it compounds the inland flooding dynamic,” she says. “That’s an area where a lot more research has to be undertaken and better modelling. It will allow us to give a better visual for people residing in those areas about the type of risk they will face.”

Ms. Riley appears proud of how scientists in the region have improved their forecasting with the use of radar and satellite imagery and modelling. The next challenge is communicating messages to the general public. She explains that success often depends on how officials format the message.

“I think that the typical person may have a challenging time visualising what a rainfall statistic means. When you send a message saying, ‘We expect to have rainfall accumulation of 10-15 inches over a 24-36 hour period,’ that’s fine for persons who are in step within the meteorology or disaster management discipline, engineers or water-related engineering. But I think when it comes to the general public, you have to translate that into some sort of a visual of what that means on the ground. If we are to be more effective with early warning systems, we have to look more deeply at the components that bring that authoritative message that is communicated to the public.“

And then there is the reality of uncertainty. Tropical storms are forming earlier and later in the season than in the past, and changes in weather patterns, likely due in part to climate change, can elude even the best forecasting technology. Riley recalls the unusually heavy rains just before Christmas in 2013 that flooded areas of St. Lucia, Dominica, and St. Vincent and the Grenadines. At least 15 people died, and hundreds more were stranded or forced to leave their homes.

With her skill at building coalitions and engaging stakeholders, Riley believes there’s still more disaster preparedness officials can do. “I think that we have to engage our media more too. I think the media is a very powerful partner in the conversation of hazards, and it’s reality that even those small severe weather events and tropical storms can have significant impacts.”