Whether COP26 was a success depends on what you are measuring and who is rendering the opinion. In terms of climate finance, the answer for SIDS is likely to be “no”. While many of the 197 countries, party to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change that ended on 12 November, made concessions in hopes of reaching consensus, in the end developed countries simply were “urged” to double funding for adaptation by 2025. There was no agreement on compensation for loss and damage to developing countries already hit by climate change.

“We are disappointed the $100 billion pledge remains outstanding, and I call upon all donors to make it a reality by next year,” Executive Secretary Patricia Espinosa said in the closing plenary. “And we all know that this is not only about the $100 billion. Initiating the process for the definition of the new global goal on finance as soon as possible is therefore critical,”

Representatives from Small Island Developing States (SIDS), Least-Developed Countries (LDCs), developed countries, and the many non-governmental organisations that work on climate finance all seem to agree on one thing: the money that already is designated for mitigation and adaptation is not making its way to the countries that need it. The Green Climate Fund was founded in 2010 as part of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and is directed to take a country-driven approach to support developing nations in curbing emissions and building resilience. It has been and continues to be criticized for its complicated and lengthy application and approval process.

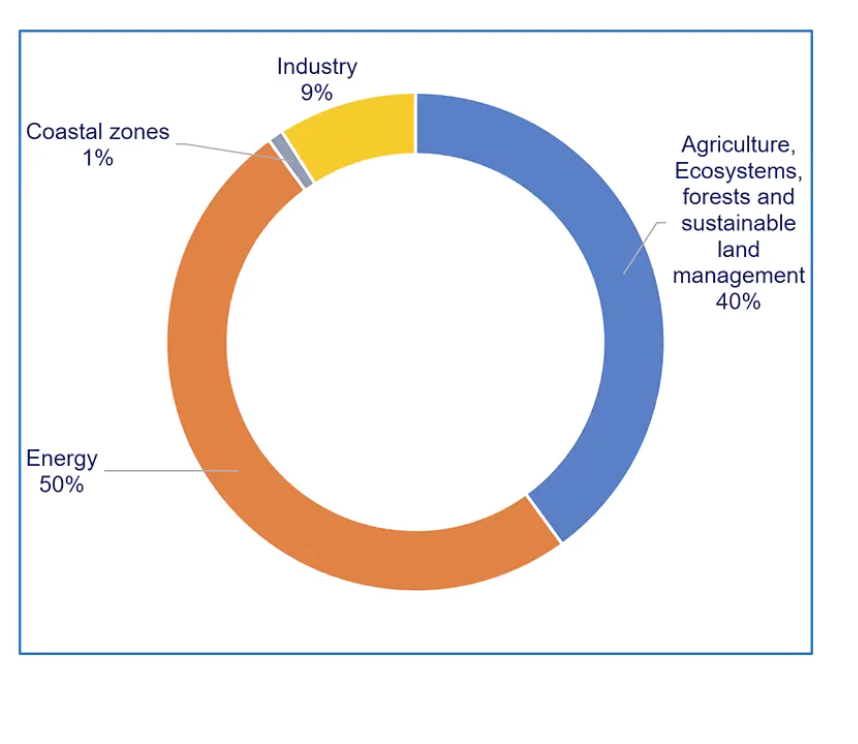

Research firm Climate Analytics found that only 18% of the US$2.54 billion approved for climate adaptation projects by the Green Climate Fund (GCF) was disbursed. The number is even lower for mitigation projects, with a mere 2% of the US$1.35 billion allocated making its way to country-led projects. Half of the money went to energy projects, 40% to agriculture, forests, and sustainable land zones. Just one percent went to coastal projects. Most of the adaptation projects undertaken by SIDS were financed by the public sector, raising the question of how to incentivise the private sector more effectively to focus more in this area. Regardless of the funding source, the disbursement rate of funds was very low, and SIDS also received the lowest share of GCF money.

Breakdown by Industry of Green Climate Fund Financing

Source: Climate Analytics

Source: Climate Analytics

Dr. Adelle Thomas, Director of the Climate Change Adaptation and Resilience Centre at the University of the Bahamas and Senior Research Associate with Climate Analytics explains, “SIDS and LDCs face a variety of constraints in accessing what funding is even available. Ministries, departments, and agencies that are responsible for accessing climate finance face challenges in their ability to prioritise, develop, and manage project concepts and to actually push them forward to approval and implementation.”

US Climate Envoy John Kerry echoed Thomas’s words, speaking about the “literally trillions of dollars” that have been pledged by the private sector. He raised the question, “How do we deploy them? How do we get them out there?…The single biggest challenge as we leave here at the end of this week is implementation.”

Hon. Diann Black-Layne, Antigua and Barbuda’s Ambassador for Climate Change and one of the lead negotiators for AOSIS, says a big part of the problem is communication. SIDS, she explains, don’t have the decades of data collection, support from hundreds of university research departments, or the depth of not-for-profit think tanks that exist in developed countries. There’s “an entire system of collecting the data, verifying the data, publishing the data, debating the information before that information is accepted as fact or fiction. We don’t have that in SIDS.” It takes thousands of dollars to train someone to participate in that system, she continues. And if a country needs to outsource data collection or buy it from an outside entity, the cost is even higher.

Ambassador Diann Black-Layne of Antigua and Barbuda (right) with Laetitia De Marez of Climate Analytics (left) at COP26 in Glasgow

SIDS are hoping for more Direct Access Entities that are local, accredited institutions such as ministries, non-profits, and private banks that can receive direct funding for projects through the Green Climate Fund. Black-Layne says these intermediaries will help developing countries verify information in a way that is standard in their culture, but which does not necessarily fit the more structured way of the US and EU countries. She says so much of the success in funding and implementing projects is due to this sort of improved communication. “Our projects, once we’ve submitted them to the Green Climate Fund…we hold our ground. And we use sayings and we use indigenous language. We use local language to make our case.”

Jamaica’s Minister of Housing, Urban Renewal, Environment, and Climate Change, Hon. Pearnel Charles, Jr. was one of many during COP26 to call for scaled-up finance for implementation of mitigation and adaptation projects. Together with the COP26 President Alok Sharma, Minister Charles announced the launch of the Partnership Action Fund, which will support NDC (Nationally Determined Contributions) enhancement and implementation by filling the gaps in the support network. Minister Charles explained that the NDC Partnership provides technical and financial support through embedded advisors who “have served as a mitochondria assisting countries to take a deeper look at the modalities that are required for them to implement the plans that we have designed.”

Hon. Pearnel Charles, Jr., Jamaica’s Minister of Housing, Urban Renewal, Environment and Climate Change, at COP26 in Glasgow.

With so much new private sector funding pledged to help SIDS and LDCs move forward on their emissions commitments and adaptation efforts, finance professionals suggest approaching funding as a multi-part or “blended finance” system. In such a system, there are different points of entry for donors throughout the project cycle from conception through approval. So, while it may be difficult to get financing for a project without a feasibility study, looking for an agency that might finance that study — the first step of the project– could be less daunting than trying to fund the entire project at once, and at the same time, could avoid delaying the project further.