A year ago, nearly to the day, scenes of chaos and destruction gripped Jamaica’s north coast as monster waves ravaged the shoreline. From Negril to Ocho Rios and beyond, seawalls crumbled, coastal roads flooded, and infrastructure in and near the sea was shredded. It was described by some as “the most bizarre flooding they have seen in decades.”

But hurricane season was months away and it wasn’t even raining. So what caused this havoc?

These damaging waves, known as Swells or Northers, occur in the Caribbean when winter storms hit North America, with an outpouring of cold air mass. These cold surges to our north create strong winds that blow over vast distances, generating waves that eventually reach Caribbean coastlines as “swell” waves, and they can be quite powerful. As the swell waves approach the shoreline they get higher, and can cause a lot damage.

Other Recent Wave Events

These Northers, or North Swells, are more common than you think. Over the last 45 years, Jamaica and the Caribbean has averaged about 14 swell events per year between November and April. The intensity varies, and typically 2 to 3 events per year stand out as being stronger than the rest.

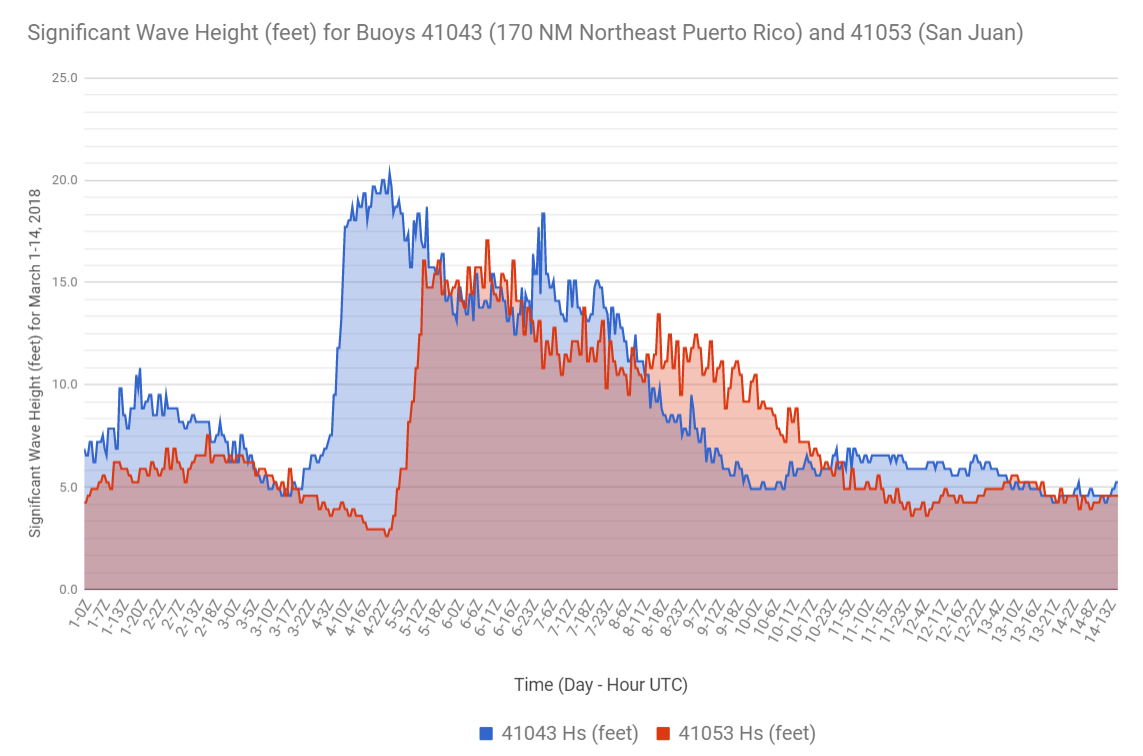

In March 2018, the eastern Caribbean experienced a Norther as severe as the one that hit Jamaica in February 2024. The 2018 event saw waves 7.5 to 9.0 metres (25 to 30 feet) high that caused widespread coastal flooding and significant erosion. Evacuations were enforced and roads were shut down in Puerto Rico and St. Thomas, USVI. Coastal roads, docks, and other seaside structures were badly damaged.

Time series of the wave heights of buoy 41043 (170 NM north-northeast of Puerto Rico) and buoy 41053 (just north of San Juan). Source: NOAA National Data Buoy Center

Data Reveals Unprecedented Wave Event

Over the past 5 years, nearly 100 Northers with wave heights from 2 to 3.5m (6.6 to 12 feet) have impacted Jamaica. Waves from these events typically affect shorelines for a day or two, but the February 2024 swell churned up seas for nearly 3 days, with waves higher than 3 meters (~10 feet) lasting more than 20 hours.

Many countries around the world track measured wave data. Unfortunately, we don’t have any permanently deployed wave instruments around Jamaica so we rely on two sources; one is the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) wave measuring buoys and the other is computer-modeled data. NOAA’s Buoy 42057, located 470 km (293 miles) south of Jamaica, showed wave heights for the February 2024 event peaking at 6.3m (20.7 feet) and lasting for about half a day. Those waves came from the northwest, which is also very unusual.

We also looked at calibrated modeled data from the European Center for Medium Range Weather Forecasts. We extracted 45 years of data from that source and our findings confirmed what a resident told us: “I’ve been living here (Montego Bay) for 50 years and I’ve never seen anything like this”. Based on numerous observations, the waves in February 2024 were among the highest to hit Jamaica’s northwest coast in at least the last 45 years. The only larger waves to affect the area were from seven hurricanes, including Ivan (2004) and Gilbert (1988). But none of these hurricanes caused waves that crashed head-on into Jamaica’s northwest coast.

In terms of the coastal damage, the February 2024 event was the worst along that stretch of shoreline in the 45 years of data we looked at. Of the 709 major wave events we analyzed from that period, only 12 came from the northwest. And of those 12, the February 2024 event had the highest waves, at more than one and a half times higher than the second ranked event. Based on these statistics, this event could be seen a 1 in 43 year event or having a 2.3% chance of occurrence.

Shifting Trends: Implications for the Future?

Our analysis revealed a worrying trend: the frequency of these major wave events is on the rise. Researchers studying Central American Cold Surges, the main driver of these occurrences in the Gulf of Mexico, have confirmed this trend. As the earth’s atmosphere warms, these cold surges are expected to occur more often but for shorter periods. Recent studies project a 10% increase in such events in the Gulf of Mexico.

Given our historical record of 12-14 events per year, this means we are likely to see as many as 20 events every year in the not-too-distant future. Moreover, larger temperature drops during these cold fronts will cause higher wind speeds and consequently more intense wave conditions.

An Urgent Call to Action

The ever-evolving impacts of climate change mean that historical data is becoming less reliable for predicting future wave events. Moving forward, there are a few things we can do to start making a difference now.

- We need to improve oceanographic data collection in and around most of the islands of the Caribbean. The current methods don’t provide the insights needed to provide Early Warning System (EWS) alerts.

- We need to establish agencies with the funding and technical expertise to do data collection, like the Institute of Marine Affairs in Trinidad and the Coastal Zone Management Unit in Barbados. Both agencies collect data on waves and beach characteristics, without which we lack the context needed to understand and predict these events. Moreover, relying only on modeled data sometimes results in an under-prediction of extreme events like the one we experienced last year.

- We need to appreciate the profound impact of cold fronts on our coastal businesses (primarily tourism) and be prepared. If we can anticipate these events and take proactive measures to safeguard non-critical assets, we can minimize downtime and potential economic losses.

- We need to rethink our design approach. While hurricanes are commonly thought to be the main threat to coastal areas, the prolonged, frequent and major impact of cold fronts cannot be ignored. Adaptation and resilience planning should encompass these less predictable but equally consequential weather events.